5 QUESTIONS with Miguel Garcia

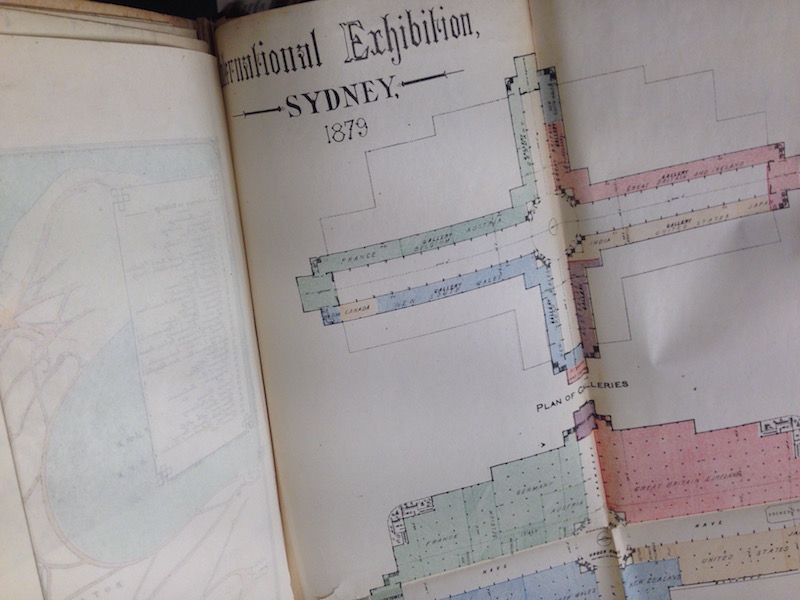

Fold-out map inside the Sydney International Exhibition catalogue, 1879

In the lead-up to Jonathan Jones’ installation barrangal dyara (skin and bones), we spoke with Miguel Garcia, Librarian at the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney, to uncover more about the history of the Garden and the 1879 Sydney International Exhibition.

What are the roles of Sydney’s Royal Botanic Garden Library and Herbarium?

We exist mainly to support the work that’s done here, by both the horticultural and scientific staff. The library itself began in 1852, about the same time that the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew began their library, so we’re as old as they are.

The Herbarium contains 1.2 million plant specimens, the oldest of which go back to the time of Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, and the actual specimens that they collected on their trip with Captain Cook. The botanical exploration of Australia paralleled the physical exploration of the continent—you can think of our library and herbarium as having a record of the earliest European engagement with Australia.

How are these archives used today?

The collections of the library and herbarium dovetail together. So a researcher can look at the specimens collected by Banks and Solander, can do DNA work on them if they want to, and then go and look at Banks’ Florilegium, which is a full-colour illustrated record of specimens made when they were collected, so they can compare them. The two collections really do speak to each other, and are inseparable, really.

What was the role of the Royal Botanic Garden at the time of Sydney’s International Exhibition in 1879? What did the gardens mean for the Colony of New South Wales?

The Botanic Garden was here not only to present the botanical wealth of the planet as it was then known to the people of New South Wales, it was there to do a much more profound work, which was to educate people on the plant species of Australia as they were found—to identify them, to make note and investigate their possible uses medicinally, culinarily or even industrially.

The tradition of economic botany, which is the exploitation of the plant world on so many different levels, began with the European exploration of the world and expanded out from there. Scientific investigation was looked on as being synonymous with cultural, social and political expansion and progress, so science and the Empire were indelibly linked.

The Botanic Gardens didn’t operate in isolation; we were in constant communication with other Botanic Gardens all round the world.

What did the Royal Botanic Garden look like for the International Exhibition? What might visitors have encountered?

What was contained in the International Exhibition wasn’t just confined to the Garden Palace building. There were numerous buildings right throughout the Gardens and the Domain, housing other parts of the exhibition which couldn’t be housed in the Garden Palace itself.

The Domain itself housed two very large buildings which showed a lot of the machinery aspects of technological progress in the Empire. You have to remember that this wasn’t confined to New South Wales, Australia, or even the British Empire. This included other countries from around the world—Japan, China, America, South American countries and other European countries. You had displays for things like religious iconographies, because they were manufactured in various parts of the world. There were examples of statuary, decorative crafts, art, and even natural and anthropological materials. The Garden Palace at one stage housed the largest and finest collection of Australian Indigenous artefacts, which unfortunately was lost in the fire.

Photograph of religious iconography on display in the Garden Palace during the International Exhibition

Are there any remnants of the Garden Palace today?

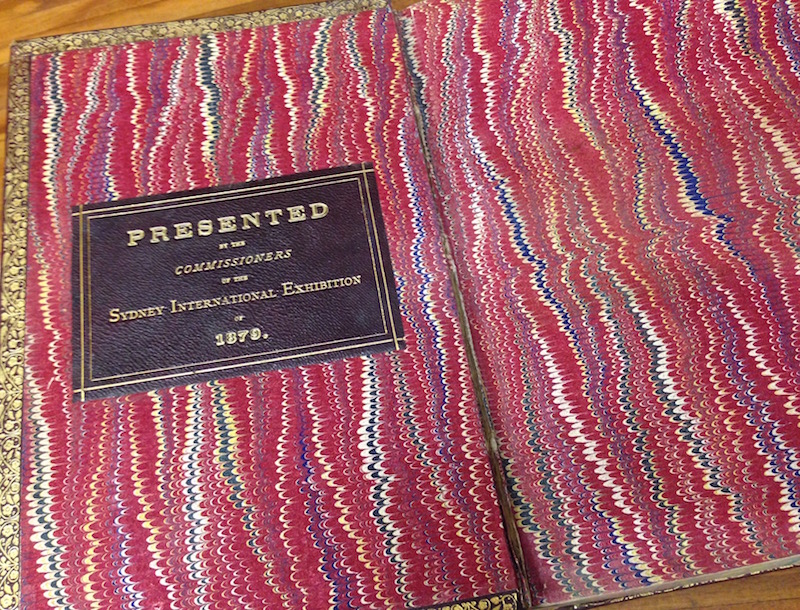

We have a deluxe copy of the International Exhibition catalogue here in the library. We also have one of two physical objects which were on display in the Garden Palace. The other one is held at the Powerhouse Museum—that’s the graphite elephant.

Here we have one of a pair of what we call the Nubian boy statues. It’s a wrought iron statue produced in France, a garden ornament. It’s a wonderful time traveller from the past. During the exhibition it was on display in the French court, where France displayed its commercial and technological produce. Either we purchased it or it was given to us, because it was easier to give away such things than incur the cost to transport them back to France. There’s always a pair of these statues by tradition, but it’s only recently that we’ve found photographic evidence that they were a pair. We don’t know where the other one has gone.

Nubian boy statue, originally displayed in the French Court, Sydney International Exhibition 1879. Now housed in the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney library

Herbarium, Royal Botanic Garden, Sydney

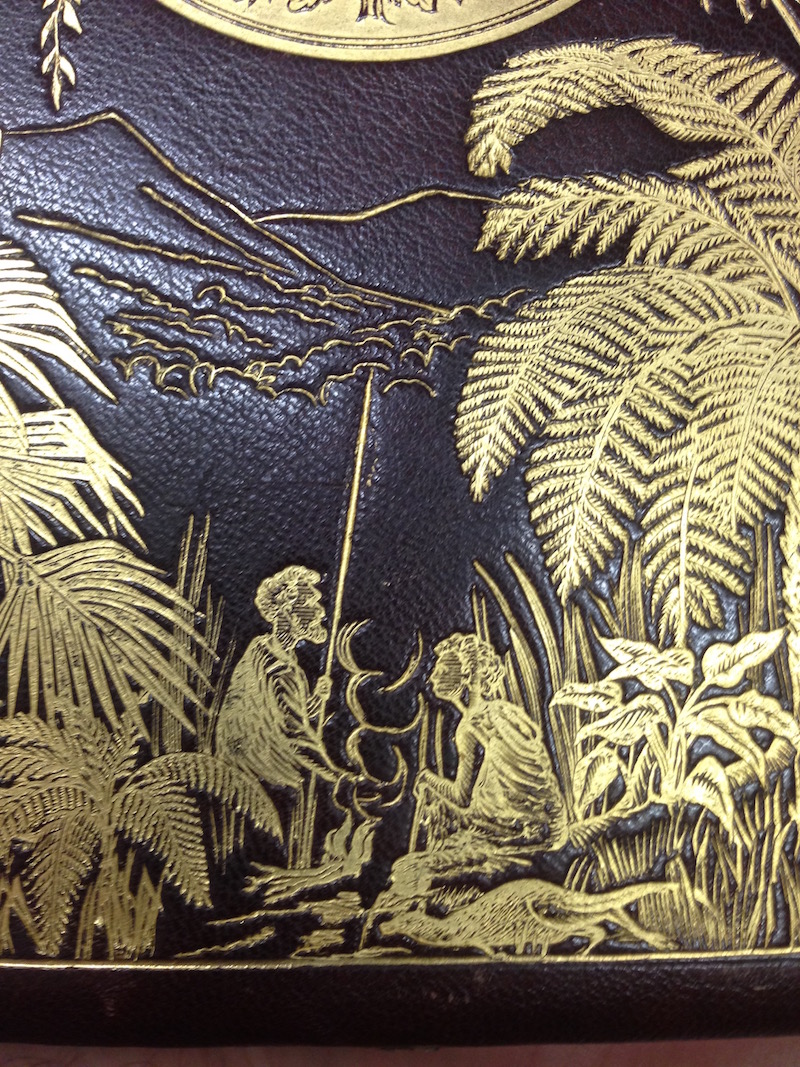

Back cover, detail, Sydney International Exhibition catalogue, 1879

Inside cover, Sydney International Exhibition catalogue, 1879